What is forks in blockchain?

A fork in the context of blockchain technology is essentially a modification to the protocol rules that results in a blockchain splitting into several possible future directions. Forks can happen for a number of reasons and result in many blockchain versions existing at the same time. This behaviour, which is controlled by the blockchain’s consensus mechanism, occurs as it develops. This article discusses blockchain splits, including what are the two types of forks in blockchain, Reasons, and implications, as illustrated below.

Soft and hard forks are the two primary types of forks. Additionally, some sources make a distinction between forks that are unintended (caused by software defects or transient conflicts) and deliberate (caused by protocol changes).

What are the two types of forks in blockchain

Soft Forks

A backward-compatible protocol modification is known as a “soft fork.” This implies that systems with outdated software or non-updated nodes can nonetheless conduct transactions with updated nodes. They apply a rule constraint, rendering blocks that were previously valid invalid. Not every miner or node has to upgrade in order for there to be a soft fork.

The blockchain network continues as a single chain after a soft fork. The upgraded nodes will impose new rules, and the lighter, unupdated nodes will not be able to contribute any blocks to the network that don’t follow them. This essentially means that nodes that have not been updated are unable to write to the blockchain any more. The Bitcoin implementation of BIP148 Segwit is used as an example.

Hard Forks

Any modification to a blockchain implementation that is incompatible with earlier versions is known as a hard fork. Hard forks, as opposed to soft forks, lessen limitations and render blocks that were previously invalid. Nodes that have not been updated will reject the blocks after the changes when a hard fork takes place. The blockchain essentially splits into two distinct blockchains with differing rules or specifications as a result of this permanent divergence. The two chains can no longer coexist.

Up to the fork, the data from the original chain is present in both new blockchains; however, neither blockchain makes use of anything that was recorded on the other after the fork. Because non-updated nodes are configured to reject any block that does not adhere to their version of the block specification, they are unable to conduct transactions on the updated hard fork chain. The community usually has to select only one of the forking paths in a hard fork, and it is not simple to switch back to the other path later with the updated specs.

In particular, a controversial hard fork happens when a backward-incompatible update is rejected by some miners, causing the network to split into two separate blockchains. Miners can choose which blockchain to support by switching to the forked blockchain’s software or by sticking with the pre-forked blockchain’s software. After a specific amount of blocks, the community frequently views the blockchain with the highest hash rate as the “winning” blockchain. Examples include the Bitcoin Cash fork from Bitcoin, the Bitcoin SV fork from Bitcoin Cash, and the Ethereum ETH/ETC split after the DAO incident.

Also Read About What Is P2P In Blockchain? Its Key Features And Advantages

Reasons for Forks

There are two basic causes of forks:

Through an update

This entails intentional, frequently planned, and coordinated modifications to the protocol rules. Disagreements among participants over the course of the blockchain’s development may be the root cause. Because participating nodes and users are known to be involved, permissioned blockchain networks can reduce the risk of forking by requiring software updates.

Accidentally

This happens when additional blocks are discovered throughout the network before a single version is completely dispersed. Consensus algorithms try to avoid this, but it can still happen, particularly in proof-of-work systems where several miners may solve the puzzle at the same time. Inadvertent forks can also result from software defects. Forks are another term for temporary ledger disputes that do not result from software changes, but occur when two or more blocks have the same block number.

Also Read About Features, Advantages Of Symmetric Cryptography In Blockchain

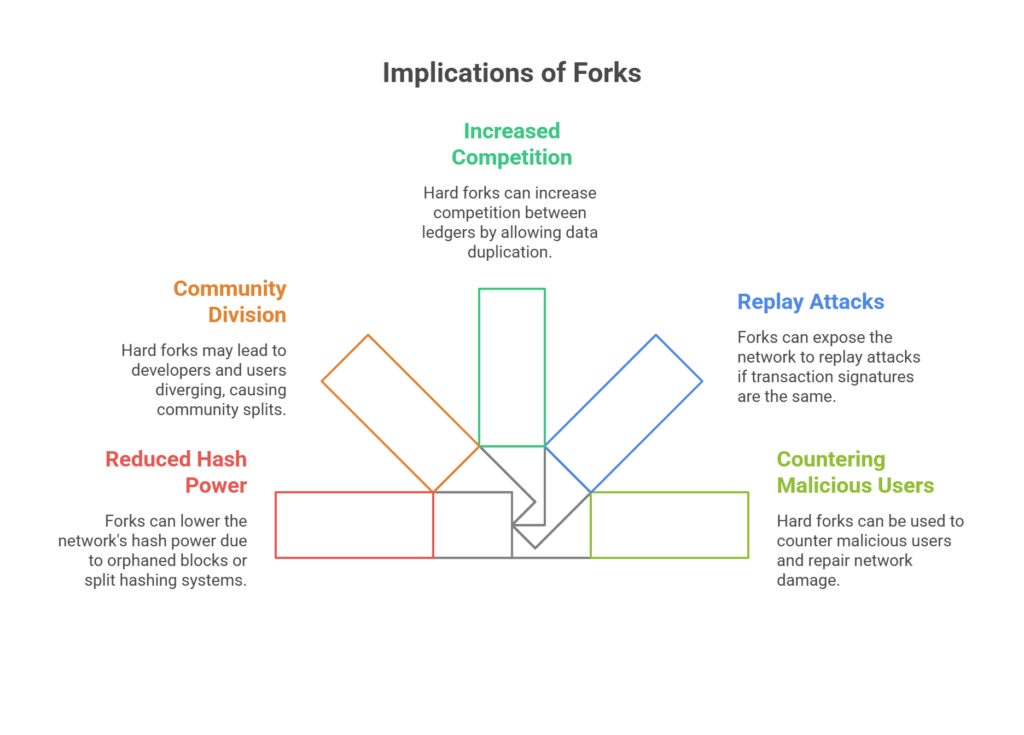

Implications of Forks

Forks affect a blockchain network in a number of ways:

- As a result of blocks becoming orphaned (in soft forks where nodes don’t update) or the systems producing hashes being split up among various chains (in hard forks), they lower the network’s hash power.

- The longest chain is usually regarded as the only version of the truth, and inadvertent forks usually end on their own when one chain becomes longer than the other. The frequency of unintentional forks is reduced through difficulty modifications.

- Developers and users may go in opposite directions as a result of hard forks, which can cause community division.

- By making it possible for data from the original blockchain to be duplicated on a rival ledger, hard forks might increase competition between ledgers. Because readers can switch ledgers without losing their “stakes” (digital assets) due to the portability of information in a hard fork, writers (validators/miners) are forced to compete by providing lower fees on the ledger that readers prefer.

- If both chains utilise the same transaction signature method, a hard fork might expose the network to replay attacks, in which a transaction on one chain could be mirrored on the other.

- Malicious users may temporarily damage blockchain networks, although they can be countered by hard forks.

Consensus mechanisms are intended to handle possible failures or malevolent behaviour that could cause splits, as well as to manage consensus within the network. While some mechanisms, like DBFT, are made to prevent forks by demanding a high threshold of validator acceptance, others, like PBFT, require view adjustments when a leader is flawed. Certain more recent protocols, such as FBFT, are made to allow forking in specific circumstances. Mechanisms intended to prevent forks are frequently an element of consensus scalability, especially in proof-of-work systems that struggle with transaction throughput and finality.