In this article, we learn about Maximal Extractable Value, how MEV works, Types of MEV, and Impact of MEV

Maximal Extractable Value (MEV)

Maximal Extractable Value

Maximal Extractable Value is a complex issue on public blockchains, especially those like Ethereum with enormous transaction volumes. Block producers (miners or validators) or other network participants may purposefully include, exclude, or change transaction sequence to maximize value when establishing a new block. This amount is on top of the regular petrol fees and block rewards.

Evolution of the Term:

As mining dominated block production and transaction ordering in Proof-of-Work (PoW) blockchains, MEV was named “miner extractable value.” Validators performed these roles after Ethereum switched to PoS in September 2022, known as “The Merge.” The phrase was changed to “Maximal Extractable Value” to reflect this larger definition and emphasise that value extraction isn’t just for miners. The term “blockchain extractable value” (BEV) has also been used in some recent articles to propose a broader meaning.

How Does MEV Work

A public waiting area known as the “mempool” a collection of pending, unconfirmed transactions, is where a user’s transaction initially goes after submission. These transactions must be verified by block producers, also known as validators or miners, before they can be grouped into blocks and put to the blockchain. In order to optimise their profit, block producers frequently give priority to transactions with the highest transaction fees (gas prices).

The requirement that transactions be chosen or arranged only on the basis of fees is not strictly enforced, nevertheless. Block producers, or other autonomous network users referred to as “searchers,” are able to extract more value because of this autonomy. In order to find lucrative MEV chances in the mempool, searchers usually use sophisticated algorithms or bots. In order to guarantee that their transactions are prioritised and completed before others in order to obtain the MEV, they then submit their own transactions, frequently paying exorbitant petrol rates. In competitive situations, searchers may prohibit producers by paying up to 99.99% of their possible profit in petrol fees.

You can also read Testnet in Blockchain Differences Between Testnet & Mainnet

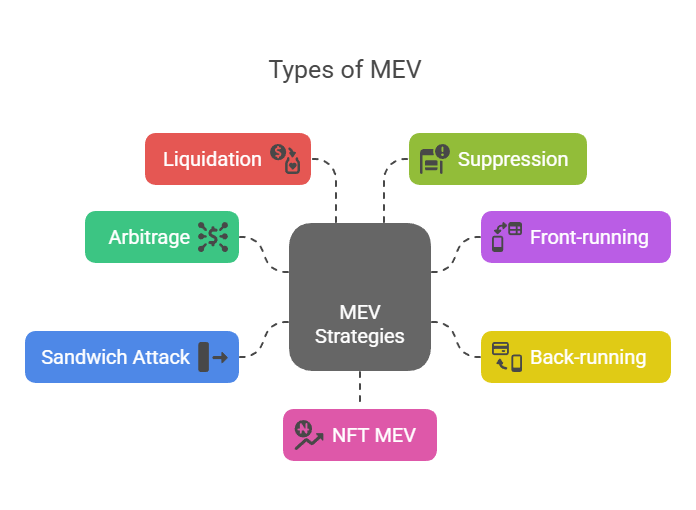

Types of MEV

Types of MEV

MEV profits are often captured through various strategies:

- Arbitrage is the practice of taking advantage of price variations for the same cryptocurrency asset on two or more decentralized exchanges (DEXs). In order to balance prices and make money, an arbitrageur purchases the item on the exchange with a lower price and sells it on the one with a higher price. These chances can be front-run or back-run by MEV searchers.

- Front-running: In order to profit from the price impact of a target transaction, block producers or searchers insert their transaction before the target transaction. This is known as a front-run trade. To get a better price, a bot might, for instance, place its own buy order right before a big buy order is seen. Generalized frontrunners only replicate and alter lucrative deals with their own address and a bigger fee; they don’t necessarily interpret the transaction.

- The reverse of front-running, back-running, occurs when a MEV actor positions their transaction right after a target trade to profit from the price movement it generates. For example, a back-runner can immediately conduct an arbitrage transaction to balance the price for a guaranteed profit following a significant swap on an Automated Market Maker (AMM) that alters the exchange rate.

- Front-running and back-running are combined in a sandwich attack. In order to profit from the initial deal’s slippage, a searcher finds a big DEX trade, makes a buy order before it to inflate the price, and then a sell order after the original trade (which further moved the price). One of the most prevalent MEV assaults, it might make the user experience worse.

- Liquidation: Under decentralized finance (DeFi) lending rules, a borrower’s position may be liquidated if market changes cause their collateral to drop below a certain level. The entity that initiates this liquidation frequently receives a payment from the smart contracts. In order to obtain this incentive, MEV actors compete to submit the liquidation transaction first, paying greater fees for priority.

- By either bribing block proposers to leave blocks vacant or by filling upcoming blocks with the MEV actor’s own transactions, suppression (also known as clogging or block stuffing) seeks to postpone or stop a user’s transaction. This uses block space to remove the intended transaction, which is frequently observed in lottery or gambling apps that give wins to the last account to enter.

- NFT MEV: Similar strategies, including guaranteeing first-in-line purchases for well-liked drops or snagging unintentionally cheap NFTs, can be used in the NFT market.

You can also read Quorum Slice: Decentralized Consensus In Distributed Systems

Impact of MEV:

MEV presents both benefits and drawbacks:

Pros:

- Market Efficiency: MEV promotes market efficiency by ensuring that prices across several DEXs stay constant, especially through arbitrage.

- Protocol Stability: When collateral falls below required levels, lenders are paid back to rapid liquidations made possible by MEV actors, which are essential to the solvency of loan protocols.

- Network Security: By encouraging block producers to secure the network, some contend that competition amongst them to authenticate transactions and capture MEV can improve network security.

Cons:

- Worse User Experience: Often referred to as a “invisible tax” or “invisible fee,” detrimental MEV kinds such as sandwich assaults cause regular users to slip more and execute trades less optimally.

- Increased Transaction Fees & Network Congestion: The bidding wars (Priority Gas Auctions, PGAs) among searchers to get their transactions included first can drive up gas prices for everyone, leading to network congestion.

- Consensus Instability & Centralization Risk: Block producers may be encouraged to reorganise earlier blocks (also known as “re-orgs”) in order to collect more MEV if the MEV extracted from a block much surpasses the typical block reward. This puts the blockchain’s consensus mechanism’s security and integrity in jeopardy. Because larger staking pools may have more resources to optimise for MEV, resulting in economies of scale and encouraging single stakers to join larger pools, MEV extraction is also thought to hasten validator centralisation in PoS.

- Permissioned Mempools/Dark Pools are created when traders send transactions straight to validators for private inclusion in order to prevent front-running. By rewarding individuals with more financial means, this can lessen Ethereum’s permissionlessness and trustlessness.

- MEV Mitigation Approaches: One crucial area of research and development is addressing the negative externalities of MEV. Among the possible remedies are:

- By dividing the responsibilities of block producers, those who schedule transactions and construct blocks, and block proposers, validators who suggest blocks for inclusion in the chain, Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS) is a crucial architecture that reduces MEV at the consensus layer. The validator proposing the next block selects the transaction bundle with the highest fee after block builders generate them and bid for their inclusion. By democratising MEV prospects, this can diminish centralisation concerns and lessen validators’ direct incentive to maximise MEV.

- Builder API (e.g., MEV Boost) is a stopgap measure for implementing PBS. Instead of constructing blocks locally, it enables validators to receive them from outside entities (builders). Validators choose the highest bid from the execution payload headers that builders send. Through the utilization of relayers to validate bundles, MEV Boost, an advancement on Flashbots, enables searchers to locate opportunities, builders to compile them, and validators to select the most lucrative block. It promotes competition and democratises MEV access, strengthening resistance against censorship.

- Fair Sequencing Services (FSS): Created by Chainlink, FSS uses decentralized oracle networks to provide equitable transaction ordering. In order to prevent front-running possibilities based on early visibility, users encrypt transactions to conceal details, which are then ordered by a decentralized oracle network and decrypted for on-chain execution. First-in, first-out (FIFO) processing is guaranteed by temporal ordering.

- Commit-Reveal schemes are a technological mechanism that keeps transaction execution and ordering apart. After registering a transaction hash, users proceed to provide comprehensive information. This prevents front-running by hiding material during ordering.

- Economic Measures: To start, users might change priority fees to affect ordering. The rise of “transaction bundles” sent straight to block proposers through “relayers” with the intention of removing priority gas auctions (PGAs) from the mempool in order to lessen competition.

- Regulatory Actions: MEV’s legal classification is a developing subject. Regulations like Europe’s MiCA, which even mentions MEV as a possible sign of market abuse, are starting to address the issue of MEV, which some view as a type of market manipulation. Due to blockchains’ global and pseudonymous nature, MEV misuse and accountability are difficult to show.

Any market actor producing blockchain-based solutions or doing commerce on public blockchains should understand MEV.

You can also read Mainnet Definition, Characteristics, How It Works & Examples