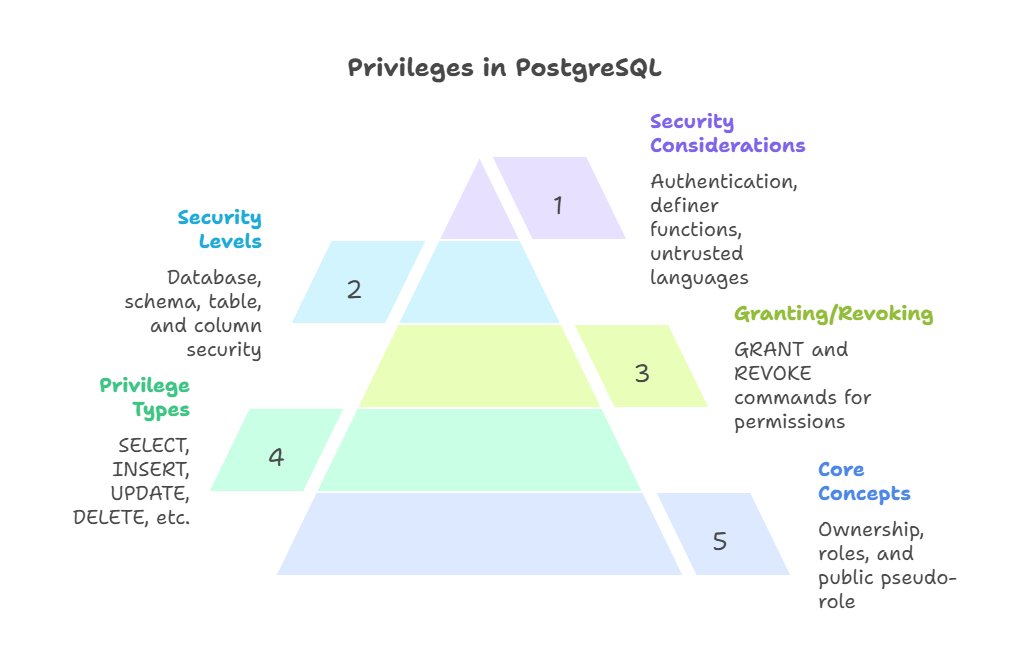

Privileges in PostgreSQL

Privileges, sometimes referred to as permissions, are essential for managing fine-grained control over database object access in PostgreSQL. Only the owner or a superuser can first act on an object after it has been created. The owner is usually the role that executed the creation statement. Privileges must be granted in order for other roles to use an object. SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, TRUNCATE, REFERENCES, TRIGGER, CREATE, CONNECT, TEMPORARY, EXECUTE, USAGE, SET, and ALTER SYSTEM are just a few of the numerous object-level rights that PostgreSQL provides. A privilege’s applicability varies according to the kind of object; for example, functions are covered by EXECUTE, whereas tables are covered by INSERT.

Privileges can be assigned using the GRANT command, which specifies the object, recipient role, and privilege type. Every role in the system can be given a privilege by using the unique “role” name PUBLIC. Furthermore, the option to grant rights “WITH GRANT OPTION” enables the receiver to further grant such privileges to other people. On the other hand, granted rights can be revoked using the REVOKE command.

Certain privileges, such as DROP and ALTER, are inalienable to the owner of the object and cannot be given or taken away. Additionally, PostgreSQL enables default privileges, which make management easier by enabling administrators to define privileges on all upcoming database assets inside a certain schema or database. You can use ALTER DEFAULT PRIVILEGES to configure these.

Core Concepts of Privileges

Ownership: Database objects like tables, views, and functions are assigned owners at creation. In most cases, the role that carried out the creation statement is the owner. It is inherent for the owner (or a superuser) to have the ability to change or remove that item as well as to give or take away privileges from others.

Roles: PostgreSQL uses the idea of roles to control access permissions. Roles can be either a database user or a group of users. Roles have the ability to provide privileges to other roles and own database objects. It is possible to grant membership in one job to another, which enables the member to utilise the parent role’s benefits.

Creating roles is done with the CREATE ROLE command. Roles that include options like LOGIN can connect to the database, although NOLOGIN roles usually work as groups. Roles may possess features like SUPERUSER, CREATEDB (for creating databases), CREATEROLE (for creating other roles), and INHERIT/NOINHERIT (for managing privilege inheritance from group roles).

PUBLIC Pseudo-Role: All PostgreSQL users have a unique PUBLIC pseudo-role. PUBLIC has numerous rights by default (CONNECT and TEMPORARY for databases, EXECUTE for functions/procedures, and USAGE for languages/data types), but they can be disabled for security.

Types of Privileges

Different kinds of privileges are supported by PostgreSQL, and each is relevant to a certain type of object:

SELECT: Select enables the use of COPY TO and the reading of data from a table, view, or materialised view. Currval is also allowed for sequences.

INSERT: A basic Data Manipulation Language (DML) command for adding new rows (records or tuples) to a table in PostgreSQL is the INSERT statement. Its main objective is to add data to a table. A list of data values that correspond to the table’s columns is contained in the VALUES clause, which is followed by the table name when executing a basic INSERT. These values, which are usually literals (constants), are listed in the table’s columns. Numerical values do not typically require single quotes, but string constants do.

UPDATE: In PostgreSQL, the UPDATE statement is a Data Manipulation Language (DML) command that is mostly used to change data that already exists in a table without altering the number of rows. The table name must be specified, the SET clause must specify which columns to modify and their new values, and a WHERE clause may be used to filter which rows are impacted. The table’s rows will all be updated if the WHERE clause is left off. Any scalar expression, including references to the current value or values of the column being updated, can be used as the new value assigned in the SET clause.

DELETE: DML commands like PostgreSQL’s DELETE statement remove rows (records or tuples) from a database table.

DELETE FROM [WHERE ] would remove rows from the specified table. The WHERE clause specifies row deletion criteria. Without the WHERE clause, all rows in the table will be erased, leaving it empty. DELETE without a WHERE clause is risky since PostgreSQL won’t ask for confirmation.

TRUNCATE: In PostgreSQL, the TRUNCATE statement is a Data Manipulation Language (DML) command that can be used to quickly and thoroughly erase every row from a table. Because it doesn’t really scan the table, it is much faster and more effective than a DELETE statement without a WHERE clause, especially for large tables.

REFERENCES: PostgreSQL foreign key restrictions maintain table referential integrity with the REFERENCES clause. Its main purpose is to match values in one column (or collection of columns) of the referencing table to a primary key or unique constraint of the referenced table. This method inhibits data production or modification that violates entity relationships.

TRIGGER: Triggers in PostgreSQL call specialised functions “fired” when a specified event occurs on a table, view, or foreign table. Active databases utilise triggers to enforce complicated business rules, maintain referential integrity beyond simple foreign key constraints, audit, and manage data consistency. They enable automated DML event responses.

CREATE: The CREATE statement in PostgreSQL is a basic DDL operation used to define and add database objects. It lets users set up data storage, management, and interaction. The large range of CREATE commands for different object types in PostgreSQL adds to its extensive SQL constructs.

CONNECT: Connecting a client application to PostgreSQL establishes a session to perform queries and handle data. PostgreSQL is a client/server database management system that accepts client connections and manages database files. Frontend applications conduct database actions. The postmaster daemon process assigns a backend server process to the client after the initial connection request.

TEMPORARY (or TEMP): The TEMPORARY term in PostgreSQL marks database objects, mostly tables, as temporary. Temporary tables are automatically deleted when the database session ends. They are excellent for short-term data management because they are not durable.

EXECUTE: Enables a function or procedure to be called. For functions and procedures, this is the only kind of privilege that is relevant.

USAGE: Assists in the creation of functions in procedural languages. permits things inside schemas to be accessed. It enables for currval and nextval for sequences.

EXECUTE: In PostgreSQL, the EXECUTE command is a flexible statement for executing SQL commands, especially when dynamic SQL or prepared statements are used in procedural languages and client applications. Its main purpose is to run a dynamically generated command string or a previously written statement.

ALTER SYSTEM: PostgreSQL’s powerful ALTER SYSTEM command changes database cluster-wide system parameters. This command allows SQL-accessible changes to postgresql.conf settings. Changes made using ALTER SYSTEM are saved in postgresql.auto.conf.

ALL [PRIVILEGES]:PostgreSQL GRANT and REVOKE commands regulate database object access rights using ALL [PRIVILEGES]. ALL gives or revokes all object type-specific rights. Use of PRIVILEGES with ALL is optional.

Granting and Revoking Privileges

A key component of database security in PostgreSQL is the ability to grant and revoke privileges, which gives administrators fine-grained control over who can access certain database objects. By ensuring that users only have the rights required to complete their responsibilities, this system preserves the security and integrity of data.

Users (or roles) on database objects can be granted particular capabilities using the GRANT command. When an object, like a table, is formed, all of its privileges are immediately granted to its owner, which is usually the role that executed the creation statement. However, these privileges need to be expressly provided in order for other roles to interact with the object. GRANT some_privilege TO some_role; is the fundamental syntax. Additionally, a privilege can be granted “with grant option,” enabling the recipient to grant the same privilege to other users. It is impossible to give away privileges like DROP and ALTER that belong to the owner of the object.

On the other hand, roles can have their previously granted privileges revoked using the REVOKE command. REVOKE some_privilege FROM some_role; is the fundamental syntax. All users who obtained the privilege directly or indirectly from the original grantee will likewise lose it if it was provided “with grant option” and is later withdrawn. When handling permissions, this cascade impact must be taken into account.

Security Levels

At different levels, PostgreSQL provides fine-grained security control:

Database Level: The database level in PostgreSQL serves as a named collection of SQL objects and a container for one or more schemas, representing a primary organisational structure. When it comes to organising things inside a PostgreSQL server instance, it is the highest level of hierarchy.

Schema Level: At the schema level, object creation and access are managed by the CREATE and USAGE rights. It is standard procedure in security to remove CREATE from the public schema from PUBLIC.

Table Level: SELT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, TRUNCATE, REFERENCES, and TRIGGER are used in tables and table-like structures.

Column Level: PostgreSQL column-level security controls access to specific columns in tables, views, and materialised views. This allows database administrators to designate which users or roles can operate on specific columns, protecting sensitive data even if a user has unrestricted access to the table.

Row-Level Security (RLS): User queries are limited to defined rows via policy-based Row-Level Security (RLS). This evaluates a Boolean expression for every row, irrespective of the usual GRANT/REVOKE rights, going beyond conventional privileges. Superusers circumvent every RLS regulation.

Important Considerations for Security

Authentication vs. Authorization: Unlike authentication, permissions restrict user activity after connecting. Pg_hba.conf defines authentication mechanisms (md5, peer, ident, trust) by host, database, and user.

SECURITY DEFINER Functions: Security definer functions use the owner’s privileges, not the caller’s. A careful security assessment is needed to prevent privilege escalation or “Trojan horse” attacks while restricting data access.

Untrusted Languages: Programming languages such as C and PL Python U that have functions that permit unrestricted memory access are referred to as “untrusted,” meaning that only superusers are permitted to write functions in them. Malicious malware cannot get past system access controls as a result.

Default Public Schema: The public schema may by default permit object creation for all users in more recent PostgreSQL versions or databases. One important security measure in multi-user situations to stop unwanted object creation is to revoke CREATE on public from PUBLIC.

Conclusion

Database security and access control in PostgreSQL depend on privileges, which allow administrators to govern who can interact with which objects and how. PostgreSQL combines security and operational flexibility by giving ownership, providing and revoking access, and using login and group roles. Row-level security (RLS), the PUBLIC pseudo-role, default privilege settings, and security definer functions increase control beyond GRANT and REVOKE commands to prevent unauthorised access and privilege escalation. A strong privilege strategy supported by careful authentication, principle-of-least-privilege role design, and schema- and object-level defaults is essential to data integrity, sensitive information protection, and user restriction to their responsibilities.