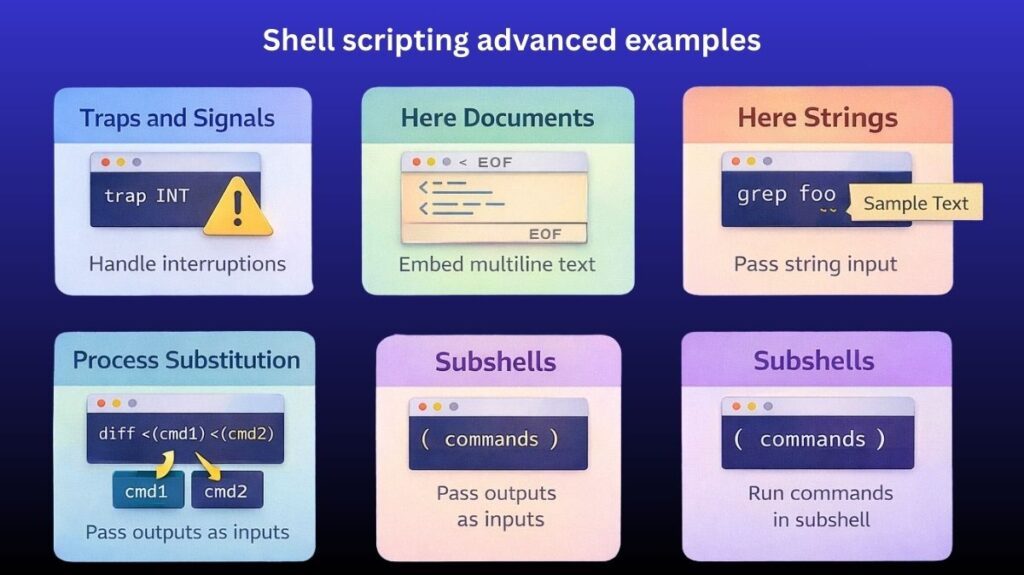

Shell scripting advanced examples

Advanced Shell Scripting entails learning how the shell controls data streams, communicates with the operating system, and responds to unforeseen disruptions, going beyond simple loops and variables.

Traps and Signals

Signals are software interrupts sent to a process to indicate an event (like a user pressing Ctrl+C). A robust script should “trap” these signals to perform cleanup tasks, such as deleting temporary files or logging a shutdown.

- Common Signals:

SIGINT(2): Interrupt from keyboard (Ctrl+C).SIGTERM(15): Termination signal (default forkill).EXIT(0): A “pseudo-signal” that triggers whenever the script finishes.

Also Read About Shell Scripting Error Handling Examples And Debugging Tools

Example: Automated Cleanup

#!/bin/bash

# Create a temp file

tmp_file="/tmp/script_data.$$"

touch "$tmp_file"

# Define the trap: remove file on exit or interruption

trap "rm -f $tmp_file; echo 'Cleanup complete.'; exit" SIGINT SIGTERM EXIT

echo "Processing data... (Press Ctrl+C to test trap)"

sleep 10Here Documents (heredoc)

A Here Document allows you to pass multi-line strings to a command without using multiple echo statements. This is commonly used for generating configuration files or displaying large blocks of text.

Syntax: << DELIMITER

Example: Generating a Web Page

Bash

cat << EOF > index.html

<html>

<head><title>System Report</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Report for $HOSTNAME</h1>

<p>Generated on: $(date)</p>

</body>

</html>

EOFUsing <<- instead of << allows you to indent your heredoc with tabs for better code readability.

Here Strings

A Here String is a stripped-down version of a heredoc. It passes a single string (or the value of a variable) to the standard input of a command.

Syntax: <<< "string"

Example: Passing variables to filters

Bash

# Instead of: echo "$VAR" | tr '[:lower:]' '[:upper:]'

# Use Here String:

tr '[:lower:]' '[:upper:]' <<< "hello world"This is more efficient than a pipe (|) because it doesn’t spawn a subshell for the echo command.

Also Read About File Handling In Shell Scripts: Read, Writing Files In Linux

Process Substitution

Process substitution allows you to treat the output of a command as if it were a file. It uses /dev/fd/<n> pipes under the hood.

Syntax: <(command) or >(command)

Example: Comparing outputs of two commands

Instead of saving command outputs to temporary files to compare them, do it in one line:

Bash

diff <(ls ./folder1) <(ls ./folder2)This feeds the output of both ls commands into diff as if they were actual file paths.

Subshells

A Subshell is a separate instance of the shell launched by the parent shell. Commands inside a subshell can modify their environment (like changing directories or variables) without affecting the parent script.

Syntax: ( commands )

Example: Encapsulating environment changes

Bash

# Start in /home/user

(

cd /tmp

touch scratch_file

echo "Current dir in subshell: $PWD"

)

# Back in /home/user automatically

echo "Current dir in parent: $PWD"Subshells vs Command Substitution

While both use parentheses, they serve different purposes:

- Subshell

( ): Executes commands in a isolated environment. - Command Substitution

$( ): Executes commands and returns the output as a string (e.g.,current_time=$(date)).

Summary Table

| Feature | Primary Purpose | Key Syntax |

| Traps | Handle signals and cleanup | trap 'commands' SIGNAL |

| Heredoc | Multi-line input redirection | command << EOF |

| Here String | Single-line input redirection | command <<< "$VAR" |

| Process Sub. | Treat command output as a file | <(command) |

| Subshells | Isolate environment changes | ( commands ) |

Shell Scripting Performance and Optimization

When scripts scale from handling a few files to processing millions of lines of data, efficiency becomes critical. Optimization in shell scripting focuses on reducing system overhead, minimizing the number of processes spawned, and leveraging modern CPU architecture through parallelism.

Avoiding Unnecessary Subshells

Every time you use a pipe (|) or put commands in parentheses ( ), the shell creates a subshell a child process. Spawning processes is “expensive” in terms of time and memory.

- The Problem: Using

catto feed a single file into a command (the “Useless Use of Cat” award).- Slow:

cat file.txt | grep "pattern"

- Slow:

- The Optimization: Use redirection or built-in arguments.

- Fast:

grep "pattern" file.txt

- Fast:

- Variable Manipulation: Use shell parameter expansion instead of calling external tools like

sedorcut.- Slow:

basename=$(echo $FULL_PATH | cut -d/ -f3) - Fast:

basename=${FULL_PATH##*/}

- Slow:

Using xargs for Resource Management

When dealing with thousands of files, a command like rm *.txt might fail with an “Argument list too long” error. xargs solves this by breaking the list of arguments into manageable chunks.

- Efficiency Benefit:

xargscan bundle multiple arguments into a single command execution, significantly reducing the number of processes started.

Example: Efficiently Deleting Files

Bash

find . -name "*.tmp" -print0 | xargs -0 rmUsing -print0 and -0 ensures that filenames with spaces or special characters are handled correctly without breaking the script.

Also Read About System Library In Linux: Definition, Types And Examples

Parallel Execution

By default, shell scripts execute commands sequentially. On a multi-core processor, this leaves most of your CPU idle.

- Using

&andwait

You can manually push tasks to the background:

Bash

for job in task1 task2 task3; do

./run_job.sh "$job" &

done

wait

echo "All jobs completed."- Using GNU Parallel

For more complex tasks, GNU Parallel is the gold standard. It automatically distributes jobs across all available CPU cores.

Example: Parallel Image Compression

Bash

# Compress all .jpg files using 4 cores simultaneously

ls *.jpg | parallel -j 4 convert {} -quality 80% {.}_compressed.jpgEfficient Text Processing

Choosing the right tool for the job is the biggest factor in performance. While the shell can read files line-by-line using a while read loop, it is incredibly slow for large datasets because the shell is an interpreted language, not a compiled one.

The Hierarchy of Speed:

- Native Shell (Parameter Expansion): Fastest for small string tweaks.

sed/grep: Fast for stream editing and searching.awk: Excellent for column-based data and basic math.perl/python: Use these when logic becomes too complex forawk.

Avoid “Looping over lines” in Bash:

Inefficient:

Bash

while read line; do

echo $line | cut -d',' -f2

done < large_file.csvOptimized (Using Awk):

Bash

awk -F',' '{print $2}' large_file.csvThe awk version can be 10x to 100x faster because it processes the file in a single optimized process.

Optimization Techniques

| Technique | Optimization Goal | Alternative to Avoid |

| Redirection | Reduce process forks | cat file | command |

| Parameter Expansion | Native string handling | echo $var | sed ... |

| xargs | Batch argument handling | Massive for-loops |

| GNU Parallel | Multi-core utilization | Sequential execution |

| AWK/Sed | Bulk text processing | while read loops |

Also Read About Process Management In Shell Scripting: Commands & Examples