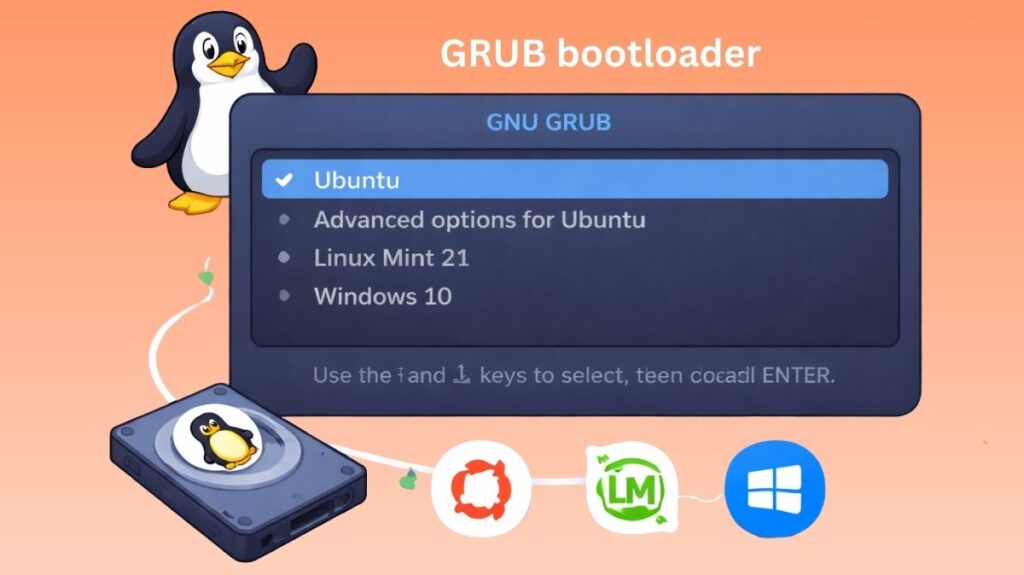

GRUB bootloader

The operating system does not launch right away when a machine is turned on. Before the OS kernel starts up, a number of things happen. The bootloader is one of the most important parts of this startup process. A bootloader is a tiny but crucial software that loads the operating system into memory and transfers control to it. The system wouldn’t know which operating system to start or how to load it if it didn’t have a bootloader.

GRUB, or Grand Unified Bootloader, is the most used bootloader on Linux-based computers. Particularly on systems that support multiple operating systems or sophisticated boot configurations, GRUB is essential to system initialization.

What is a GRUB?

The GNU Project created the robust and adaptable bootloader GRUB (Grand Unified Bootloader) . Its main duty is to start the boot process and load the Linux kernel into memory. In contrast to previous bootloaders, GRUB can recognize file systems, show interactive menus, and let users select between several kernel or operating system versions during launch.

GRUB is compatible with both vintage and current hardware because it is made to run on both BIOS-based and UEFI-based systems. The majority of Linux distributions, including Ubuntu, Debian, Fedora, and Arch Linux, now utilize GRUB as their default bootloader since it is extremely flexible and constantly maintained.

How GRUB Works

The bootloader operates in phases because it needs to read complicated filesystems and fit into small disk areas (like the MBR):

Stage 1: The first 512 bytes of the disk (MBR) or the EFI System Partition contain a little piece of code. Pointing to Stage 1.5 or Stage 2 is its only responsibility.

Stage 1.5: Contains the drivers (such as ext4 or xfs) required to read the filesystem. GRUB can now “see” the /boot folder to this.

Stage 2: This is GRUB in its entirety. After reading the (grub.cfg) configuration file, it shows the menu and awaits your input.

Role of GRUB in the Linux Boot Process

When hardware initialization is finished by the system firmware (UEFI or BIOS), Linux boots up. Control is then transferred to the bootloader. GRUB is useful in this situation.

The Linux kernel image is found on the disk and loaded into system memory by GRUB. The initramfs, which includes crucial drivers needed for early system startup, is loaded by GRUB in addition to the kernel. GRUB’s involvement in the boot sequence ends after this loading process is finished and the kernel takes over.

GRUB’s function is crucial even though its execution time is brief. The machine may not boot up if there is a GRUB configuration or installation error.

- A list of installed operating systems is shown by the menu provider (dual-booting).

- The Linux kernel (vmlinuz) and the initial RAM disk (initrd) are loaded into the system memory by the kernel loader.

- Specific instructions, such as “boot in quiet mode” or “mount the drive as read-only,” are passed to the kernel via parameter passing.

Why GRUB Is Important

GRUB is more than a loader for kernels. It offers control and flexibility when the system first boots up. Booting different operating systems from a single workstatioACn is one of its most significant benefits. From the GRUB menu, users can choose Linux, Windows, or many Linux kernels.

GRUB facilitates troubleshooting and recovery as well. Users can choose an older, more reliable kernel from the boot menu if a recently installed kernel doesn’t start. Expert users can manually change the boot parameters during launch, which is particularly helpful for testing configurations or resolving system difficulties.

Also Read About Difference Between BIOS And UEFI In Modern Computers

GRUB Interfaces

GRUB (GRand Unified Bootloader) actually offers three different interfaces based on the system’s condition and the user’s requirements, however most users only see the normal menu upon startup. A whole system reinstall or a short remedy may depend on your ability to comprehend these.

The Menu Interface (The Standard View)

When a dual-boot computer is turned on, this is the graphical or text-based menu that appears. It is made to be straightforward and simple to use.

- Function: Gives you the option to choose the kernel or operating system version to boot.

- Key Action: You can temporarily change the boot settings by pressing the ‘e’ key on a selected entry (e.g., adding

nomodesetto remedy graphics difficulties orinit=/bin/bashto reset a lost password).

The Menu Editor Interface

You can access the Editor by pressing the ‘e’ key in the Menu Interface. This setting is straightforward and resembles a notepad.

Function: To alter the boot instructions momentarily for a single session.

Common Use Case: To conceal or display system messages at boot, switch the “root” device or add kernel settings like quiet splash.

Commands: To boot with the changed settings, use Ctrl+X or F10; to undo the changes and go back to the menu, press Esc.

The GRUB Shell (Command Line Interface)

The most potent and frightening aspect of GRUB is this. Pressing ‘c’ at the boot menu opens what appears to be a terminal. Your system will immediately dump you into this shell if it is unable to locate its configuration file.

Prompt: grub>

Function: The boot process can be directly controlled by hand. You can “hand-start” the kernel, locate partitions, and manually load modules.

Essential Commands:

ls: Lists all available partitions (e.g.,(hd0,gpt1)).

set: Displays system variables.

insmod [module]: Loads specific drivers (likefatorntfs).

Also Read About Difference Between MBR Vs GPT Partition in Operating Systems

The “Rescue” Mode (The Emergency Shell)

You see a simplified version of the shell if GRUB is seriously broken or if its “Stage 2” files are absent.

Prompt: grub rescue>

Capability: Very limited. It only supports basic commands to help you find the partition where the rest of GRUB’s modules live.

Recovery Steps:

1. Use ls to find your Linux partition.

2. Use set prefix=(hdX,Y)/boot/grub to point to the configuration.

3. Use insmod normal followed by normal to try and bring back the standard menu.

Comparison of Interfaces

| Interface | Access Key | Use Case |

| Menu | Automatic | Selecting OS or Kernel. |

| Editor | e | Fixing temporary boot/driver issues. |

| Full Shell | c | Advanced troubleshooting and manual booting. |

| Rescue Shell | Automatic (Error) | Repairing broken bootloader paths. |

Also Read About Explain Different Types Of Linux Shells In Operating System

Important GRUB Files

As a Linux user, you should know where the “brain” of GRUB lives. Note: Never edit the grub.cfg file directly.

- /etc/default/grub: The main file where users can change settings (like timeout duration or background images).

- /etc/grub.d/: A folder containing scripts that build the final menu.

- /boot/grub/grub.cfg: The actual configuration file read by the system. It is automatically generated.

- update-grub: The command used to “save” your changes after editing

/etc/default/grub.

Useful GRUB Terminal Commands

If your system fails to boot, you might find yourself at a grub> prompt. Here are the tools to manage it:

| Command | Purpose |

ls | Lists all drives and partitions (e.g., (hd0,msdos1)). |

set | Shows current environment variables like where the root is. |

insmod | Loads a specific module (driver). |

sudo update-grub | Updates the boot menu after a kernel update. |

grub-install /dev/sda | Reinstalls the bootloader to a specific drive. |

Common Troubleshooting

The “GRUB Rescue” Screen

If you see error: no such partition followed by a grub rescue> prompt, it means GRUB can’t find its configuration files. This usually happens if you deleted or moved the partition where Linux was installed.

Fixing a Broken Bootloader

If Windows overwrites your Linux bootloader (common in dual-booting), you can use a Live USB to “chroot” into your system and run:

sudo grub-install /dev/sdX

sudo update-grub

Also Read About What Is The Difference Between Linux And Windows? Explain

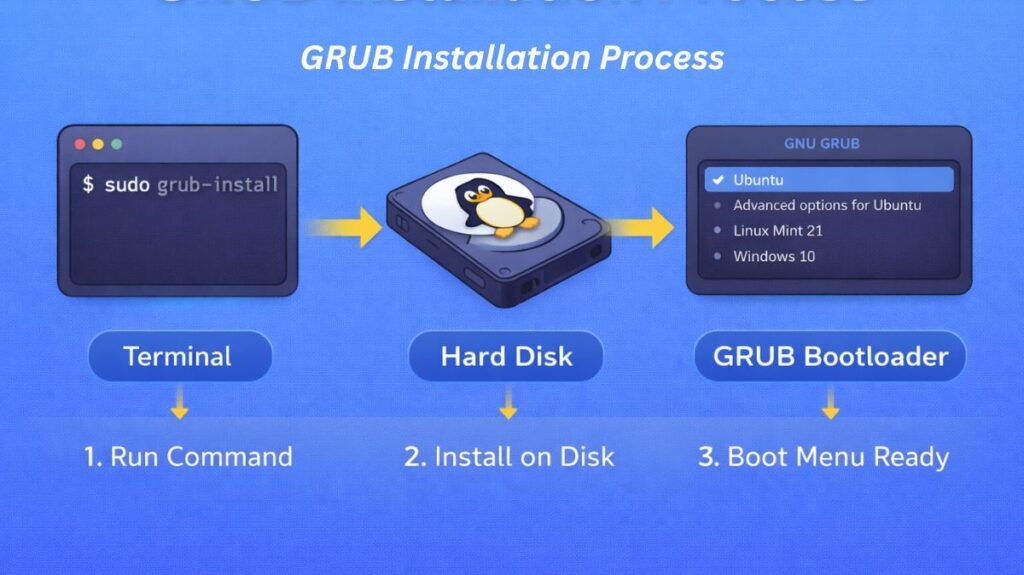

GRUB Installation Process

The last crucial bridge in a Linux installation is GRUB installation. It guarantees that the firmware is aware of the precise location of the operating system when your machine is restarted. Modern computers (UEFI/GPT) and older ones (BIOS/MBR) have different procedures.

Installation on UEFI Systems (Modern)

On contemporary hardware, GRUB resides as an.efi file inside a unique partition known as the EFI System Partition (ESP) rather than simply in a hidden sector of the disk.

The Steps:

Mounting the ESP: The installer finds the FAT32 partition, which is typically 512 MB in size, and mounts it to /boot/efi.

Copying Binaries: GRUB copies its EFI application to /boot/efi/EFI/[distro_name]/grubx64.efi.

Registering with NVRAM: This is the “magic” step. The installer uses a tool called efibootmgr to tell the motherboard’s firmware: “Hey, there is a new boot option here. Please add it to your startup list.”

Installation on BIOS/Legacy Systems (Old)

The bootloader files do not have a “partition” on older systems. GRUB must instead cram itself into the limited hard disk space.

The Steps:

Stage 1 (The MBR): The first sector of the hard disk, known as the Master Boot Record, is where GRUB puts its first 446 bytes. This code only points to the next step because it is too little to accomplish anything else.

The “Post-MBR Gap”: The “Post-MBR Gap” occurs when GRUB installs its filesystem drivers in the vacant area that exists between the first partition’s beginning and the MBR.

Step 2: GRUB may finally access the /boot/grub folder on your Linux partition to load the menu after the drivers have been loaded.

Also Read About What Is Kali Linux And How Does It Work? Its Key Features

The Configuration Step (grub-mkconfig)

It’s only half the fight to install the files. Additionally, GRUB requires a “map” of the various operating systems and kernels.

A script known as os-prober is triggered by the command grub-mkconfig -o /boot/grub/grub.cfg (or update-grub on Ubuntu). All of your hard disks are scanned by this script for:

- Different Linux kernels.

- Boot Manager for Windows.

- Other versions of Linux (if you’re triple-booting).

All of these entries are subsequently written into the final grub.cfg file that appears at boot.

Manual Installation Commands

You would run these commands from a Live USB if you ever needed to reinstall GRUB (for instance, if Windows erased your boot menu):

For UEFI:

Bash

sudo grub-install --target=x86_64-efi --efi-directory=/boot/efi --bootloader-id=GRUBFor BIOS:

Bash

sudo grub-install /dev/sda # (Note: installing to the disk, not a partition)| Feature | BIOS Installation | UEFI Installation |

| Location | MBR (Sector 0) | EFI System Partition (File) |

| Space | Very Limited | Spacious (FAT32 partition) |

| Firmware Link | Automatic (Hardcoded) | Requires efibootmgr registration |

| Disk Type | MBR | GPT |

Also Read About What Is Ext4 File System In Linux? Features And Advantages